The concept of a “51% attack” has been part of the cryptocurrency vocabulary for more than a decade, it is often framed as a catastrophic scenario: a single actor seizes control of a blockchain, rewrites transaction history, and undermines trust in the system.

The mechanics behind such an attack method are real, but its practical implications are narrower than the term suggests.

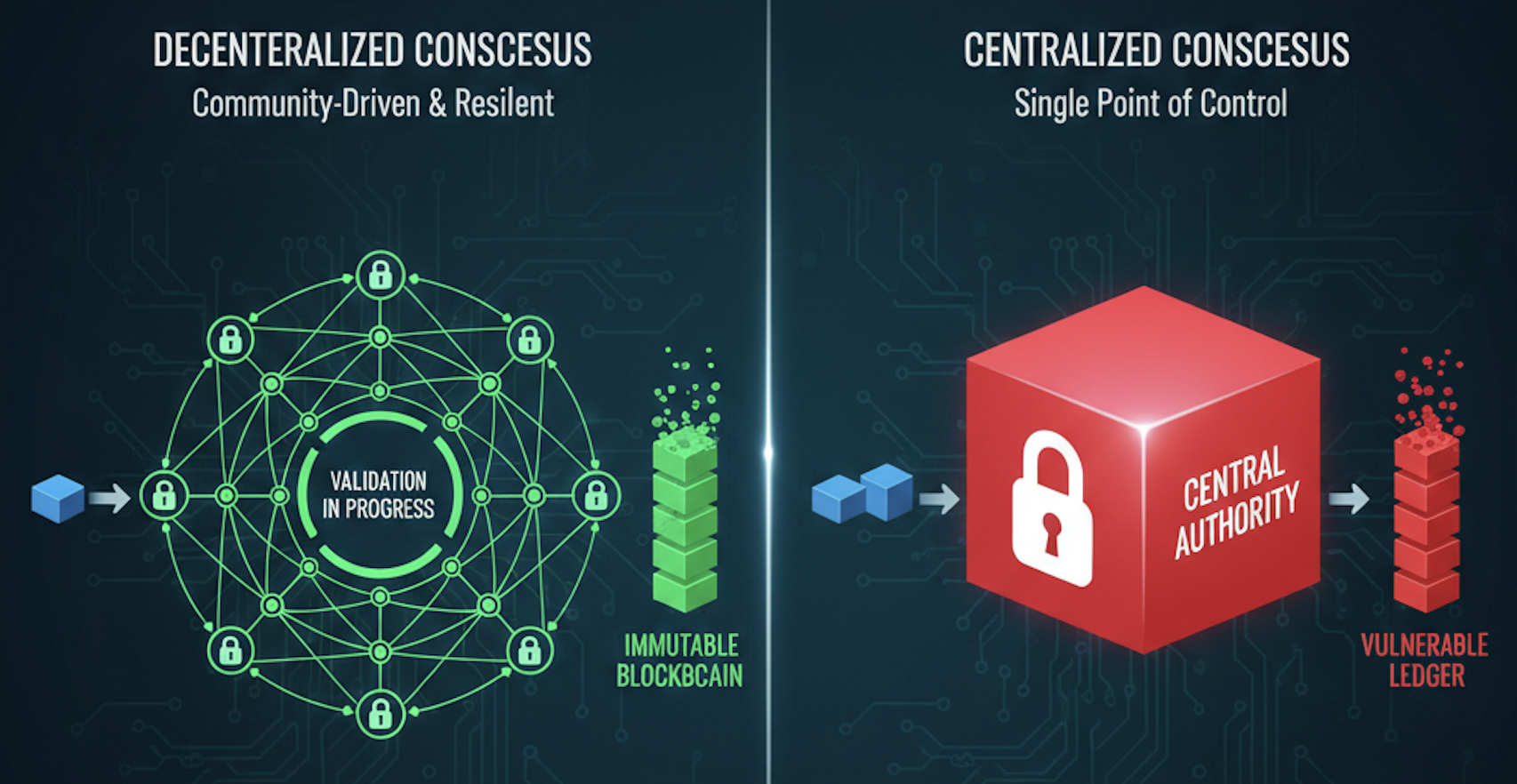

Blockchain consensus and immutability

A blockchain operates as a distributed ledger, where every participant, called a node maintains a copy of the transaction history. Consensus mechanisms allow these nodes to agree independently on the state of the ledger without a central authority. Each block is cryptographically linked to the one before it, creating a chain that is effectively immutable once confirmed multiple times.

A 51% attack targets this system by giving an attacker majority control over the network’s hashing or staking power.

With this control, they can attempt to introduce an alternate version of the blockchain. In practice, altering historical transactions remains extremely difficult: the deeper a block is in the chain, the harder it becomes to rewrite. Checkpoints in networks like Bitcoin render older blocks effectively permanent, even if attackers control a majority of the network temporarily.

Consensus ensures that the network collectively validates transactions, while cryptographic linking and depth of confirmations protect the ledger from manipulation, making successful 51% attacks feasible primarily on smaller or less-secure networks.

How consensus functions on public blockchains

Public blockchains operate without a central authority. Transaction ordering and validation are handled collectively through a consensus mechanism that defines which version of the ledger is accepted by the network.

Consensus is the protocol-level process that allows independent nodes in a blockchain network to agree on a single, valid version of the ledger, despite operating without a central authority.

In proof-of-work systems such as Bitcoin, miners compete to solve cryptographic puzzles and add new blocks to the chain. The network follows the chain that represents the greatest cumulative amount of computational work. This rule is designed to make rewriting history increasingly difficult as new blocks are added.

Each additional block layered on top of a transaction reduces the probability that it can be reversed. This is why exchanges and payment processors require multiple confirmations before treating a transaction as final. A 51% attack targets this process by attempting to overpower the chain-selection rule itself.

What majority control actually enables

A 51% attack occurs when a single entity or coordinated group controls more than half of the network’s block production capacity.

In proof-of-work systems, that capacity is measured in hash rate.

In proof-of-stake systems, it is measured by the proportion of tokens staked.

With majority control, an attacker can influence which blocks are added to the chain and which are excluded. The most common technique involves mining a private version of the blockchain that omits certain transactions, then releasing it once it becomes longer than the public chain.

When nodes encounter two competing chains, they accept the longer valid one. This can cause recent transactions on the discarded chain to disappear from the ledger.

The primary financial risk created by this behavior is double-spending.

An attacker can send funds, allow the transaction to appear confirmed, and later replace it with a conflicting transaction that redirects the funds elsewhere.

The scope of this power is limited. A majority attacker cannot bypass protocol rules, generate new coins, or seize assets from other users’ wallets. Older transactions buried under many confirmations also remain impractical to reverse without sustained dominance over long periods.

An attacker does not need absolute control of 51% of a network’s mining power to attempt an attack, but without sustained majority control, the chances of success drop sharply.

Cost, coordination, and diminishing returns

The feasibility of a 51% attack depends heavily on network size.

On large proof-of-work networks, acquiring sufficient hash power is extremely expensive. Bitcoin’s mining infrastructure spans millions of specialized machines distributed across regions, operators, and energy markets. Replicating or overtaking that capacity would require massive capital outlays and logistical coordination.

Hashing power can be rented on open marketplaces for short periods, allowing temporary majority control without long-term capital commitments.

Even short-lived attacks face operational challenges. Exchanges monitor chain reorganizations in real time and can respond by halting deposits or increasing confirmation requirements. As disruptions grow more visible, the window for extracting value narrows.

Why smaller networks face higher exposure

Most confirmed 51% attacks have occurred on smaller proof-of-work chains with limited hash rate. These networks are more vulnerable because the cost of acquiring majority control is lower, particularly when their mining algorithms are compatible with rented hash power services.

In several documented cases, attackers repeatedly reorganized blocks to exploit exchanges that accepted deposits with minimal confirmations. Once these weaknesses were identified, exchanges adjusted their policies, reducing the effectiveness of subsequent attempts.

A network defended by a broad base of independent miners or validators presents a far higher barrier to attack than one with thin economic activity.

Mining pools and perceived concentration in Bitcoin

Concerns about Bitcoin often focus on mining pool concentration. A small number of pools regularly account for a significant share of total hash rate, leading to claims that control is already centralized.

Mining pools, however, coordinate block production without owning the underlying hardware. Individual miners can switch pools quickly if incentives change or trust erodes. Pool operators rely on continued participation rather than coercion.

This arrangement creates a distinction between coordination and control. While pools influence short-term block distribution, sustained malicious behavior would likely trigger rapid hash power migration away from the offending pool.

As a result, concentration metrics alone do not fully capture the network’s ability to respond to abnormal behavior.

How proof-of-stake changes attack incentives

Proof-of-stake systems replace computational effort with capital commitment. Validators lock tokens as collateral and participate in block production according to protocol rules.

Executing a majority attack in this context requires acquiring a substantial portion of the circulating supply. Large-scale accumulation tends to be visible on-chain and can affect market prices, increasing acquisition costs.

Modern proof-of-stake networks also enforce penalties for misbehavior.

Validators that attempt to reorganize finalized blocks or violate consensus rules can lose part or all of their staked assets through slashing mechanisms.

This shifts the risk profile of attacks. Instead of expending external resources like electricity, attackers put their own capital directly at risk. The economic consequences are immediate and internal to the system.

Proof-of-stake networks are also theoretically vulnerable to majority attacks, but the economics differ sharply from proof-of-work.

On Ethereum, an attacker would need control of more than half of all staked ETH to influence block finalization by accumulating the majority of attestations, which consensus clients use to determine the canonical chain.

Unlike proof-of-work, however, proof-of-stake allows social and protocol-level responses. Validators, applications, exchanges, and infrastructure providers can coordinate to continue building on an alternative chain, while the protocol itself can penalize or remove malicious validators, destroying their staked capital. These mechanisms significantly raise the financial risk of attempting a majority attack.

When irregular behavior occurs, participants can adjust software defaults, raise confirmation thresholds, or temporarily restrict transaction acceptance. These responses do not require formal governance structures and can emerge organically.

Disclaimer: All materials on this site are for informational purposes only. None of the material should be interpreted as investment advice. Please note that despite the nature of much of the material created and hosted on this website, HODL FM is not a financial reference resource, and the opinions of authors and other contributors are their own and should not be taken as financial advice. If you require advice, HODL FM strongly recommends contacting a qualified industry professional.